|

We are all carrying a heavy burden right now.

We have engaged in this distance learning experiment with a begrudging willingness because we love our children, because we care about their education and want them to succeed. We do this because we understand the necessity of social distancing and want to do our part. But sometimes, it’s a real bitch. Right now, I am watching my child smash her fists into her computer keyboard while she screams at the screen that the computer is wrong, that she did type the correct answer to that math problem. Her breathing is fast. Her cheeks are red. She’s near tears. Governor Walz just announced that Minnesota schools will be closed for the rest of the year. So I will have to go through this with her every single weekday until June. I’m near tears myself. I know my child doesn’t behave this way at school, even when she’s frustrated with the work. She has always struggled with math--she receives reduced assignments and extra help from a para, but in spite of this, I have always heard reports of her “cheerful” disposition. It’s hard to imagine that when she is punching her tiny fist into the “frickin’ stupid” textbook. Her words. (Mine, too, if I’m completely honest.) Even though I was quite good at math in school, even though I am explaining this as clearly as I know how, even though I am a teacher by trade, I have no idea how to help her learn this stuff. My explanations and efforts are not enough to make her understand. I have a teaching degree and over a decade of experience. I have cried after a day of teaching exactly one time--my first (and last) day as a kindergarten substitute on the east side of Des Moines. That venture included no class roster, no seating chart, no lesson plans, no paras, no help of any kind, just me and 30+ screaming, combative five-year-olds who knew entirely too much about domestic violence, reproductive organs, and curse words and not nearly enough about sitting down and shutting up. It was like trying to herd cats that were both tweaking on meth and lit on fire. When I signed out for the day, I was in tears. I told the secretary to never call me again, and she glibly responded, “Yeah, we hear that all the time. No one ever comes back to sub here.” I am no stranger to difficult teaching scenarios. I am battle proven. I have earned my stripes. But this--working one-on-one with my own child--somehow feels more overwhelming than anything I’ve dealt with before. I have cried more times over teaching in the past month than in the past decade. There are days when I would prefer herding those flaming meth-cats to helping my own child solve an algebraic equation. I feel a lot of guilt about this, and the only reason I can come up with for why this seems to be true is this: It is very, very hard to be Mom and Teacher at the same time. It also seems to be very, very hard to be both Daughter and Student at the same. In a simpler time, we played these roles separately. When we were together, I was merely Mom and she was merely Daughter. If I helped her with school work, it was as Mom: my role was only to ensure that she completed it, not to step her through the entirety of the lesson. I did not have to be Teacher, and she did not have to be Student. She was just Daughter. Student and Daughter are two conflicting identities. Daughter whines and throws her books across the room. Daughter rips up papers and screams at Mom. But Student, I am told, is "pleasant." Student is “a ray of sunshine” who is "cooperative" and "well-behaved." I guess I wouldn't know. Daughter pushes Mom’s buttons. Daughter tests Mom's boundaries. Daughter has always taken out the school day’s frustrations on Mom. Daughter uses Mom as an emotional punching bag. Teacher has thick skin. Teacher knows not to take harsh words from kids personally. Teacher is professional and strong. Teacher maintains an emotional distance. But Mom cannot seem to do any of these things. Mom’s skin is onion-paper thin because Mom is completely in love with Daughter. Mom takes every harsh word she utters like a dagger to the heart. Mom is vulnerable. Mom is emotional. To be honest, Mom is kind of a mess. When Mom wants to quit, Teacher wants to keep going. When Teacher says, “It’s time for school,” Mom wants to give up, to throw that “frickin’ stupid” math book across the room and light it on fire. It is a strange tug of war within me. Sometimes Teacher wins. Sometimes Mom. Teacher is oil and Mom is water. They can be poured into the same vessel and shaken, but they will never fully combine. Many days, I am overwhelmed by this strange solution that I carry within me: the oil of Teacher and the water of Mom. That oil sits on top in fat, round globs, covering the water in a slick layer, but the water of Mom always is beneath it, bearing the burden of its weight. They are meant to be separate things, Mom and Teacher. But for now, they must coexist.

0 Comments

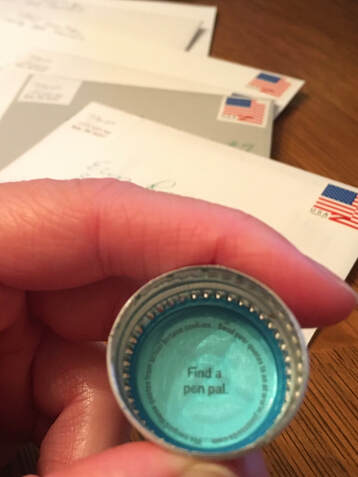

We live in a transformation-obsessed society. We're all addicted to YouTube makeup tutorials, HGTV renovation shows, and TLC 500-pound weight loss documentaries. (I stand guilty as charged on all counts.) We love them because of the quick results--we know that there will be a dramatic reveal at the end of the episode. Yes, we love our transformations. But transformation in real life is never quite so fast. (Unless you’re Jesus.) No one ever gets the immediate gratification of a real-life 45-minute kitchen renovation. Transformation is slow. Transformation takes time. Easter is all about new life and transformation, but this year, that was hard to envision, with another month of COVID-19 shelter-in-place ahead, making April feel like a rerun of March. There were no green buds on display this Easter Sunday. Instead, any and all evidence of nature’s transformation was covered in a white shroud of snow. This year, instead of transforming myself into my Sunday best for a church service, I spent Easter Sunday in my pajamas with my dirty hair thrown up in a mess on top of my head. There was no new dress to put on, no makeup to apply, no hairstyle to fuss over, no uncomfortable shoes to squeeze into. There was no Easter feast at Grandma’s house. I did my best to transform what I had into a passable holiday meal, but it was nothing compared to the juicy ham and fluffy mashed potatoes and decadent pies that I’m used to. There was no family gathering this year. Instead, I spent the day FaceTiming with my family. This was actually fabulous, and the two-hour call felt like 15 minutes. It was surreal, like watching a home movie in real time. I got to see my two-week old niece and her two-year-old sister. I got to see my grandma, my parents, my sisters. And, because of COVID-19, I got to see my brother, who is rarely present at family gatherings because of his work schedule. We spent at least half an hour of that FaceTime call listening to my brother, now out and proud, discussing wedding plans with his partner. A decade ago, this would not have been possible. He was a different person then, closeted, wrapped in the death shroud of heternormativity. It was not until that pretend self had died that he could emerge anew, truly himself, fully transformed. A lot of transformation can happen in ten years. I spent Easter Sunday contemplating the Divine transformation of death into life. I spent Easter Monday contemplating transformation of another sort. I'm a huge Jones Soda fan. I love the messages printed inside of their bottle caps. Sometimes they feel almost prophetic. On Easter Monday, the message printed inside my bottle cap suggested that I find a penpal, so I put out a call on social media to find out who wanted letters, and I had enough responses to keep me busy for seven straight hours. A few of them went to friends and family, but most of those letters went to former students, which was so sweet. Back when I was teaching, I wrote a letter to every student in their senior year, and it was my absolute favorite thing I did as a teacher. It was an unexpected blessing to revisit the experience and write to them again as adults. Perhaps it was even more gratifying the second time around. They’re truly grown-ups now, with responsibilities, with jobs and mortgages and electric bills, even with children of their own. But in my mind, they are forever 17, dressed in ratty hoodies and skinny jeans, their hair hanging in their eyes, just long enough to hide the self-hatred and depression. The anxiety and fear. The isolation and defeat. I thought about this as I wrote, and I realized that many of the burdens that they carried as teenagers have died away and transformed into something new and beautiful: self-hatred into self-acceptance. Depression into joy. Anxiety into peace. Fear into confidence. Isolation into community. Defeat into capability. They have each gone through their own unique cycle of death and resurrection. Glory, hallelujah. These transformations happened so gradually that I almost missed them. In fact, if I hadn’t written those letters, I probably wouldn’t have thought about them at all. We are so used to our heavily-edited television transformations, the kind that cut out the wait time and deliver results on demand in a neat 45-minute package. It’s easy to dismiss a change if it isn’t an immediate one. We want the jaw-drop of the before and after contrast, not the gradual slope of slow change. But the gradual slope of slow change is what we usually get. A transformation is still a transformation, no matter how long it takes. We all "are being transformed into the same image from glory to glory, just as by the Spirit of the Lord." (2 Corinthians 3:18) From glory to glory. Little by little. A thousand tiny deaths followed by a thousand tiny resurrections. Slowly, gradually, mystically. This is the miracle of Easter. Glory, hallelujah. But we all, with unveiled face, beholding as in a mirror the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from glory to glory, just as by the Spirit of the Lord.  I have found that one of the most dangerous and unproductive sentences in the English language is this: It wasn’t supposed to be this way. We all have an idea of how life is “supposed to be." There’s an order to things, a societal flow, a rhythm of expectations: school, college, marriage, career, kids, grandkids, etc. You know, the way things are “supposed to be.” With this rhythm in mind, I made plans for my life, and I was certain that things would unfold just as I had imagined they would. And for a while, they did. My own “supposed to be” started to swerve a bit at college, but it jumped the tracks at career, slammed into the ditch at infertility, and burst into flames at epilepsy. It wasn’t supposed to be this way. And now, we find ourselves in the midst of a crisis: COVID-19. Social distancing. Distance learning. Face masks. Plans postponed indefinitely. Society itself is on hold. All of our best-laid plans gone awry. When this crisis hit, I was directing a high school production of Peter Pan. We’d been practicing five days a week since January. Though the set is finished and the costumes are ready, the auditorium sits empty. We were supposed to perform it next weekend. The kids won’t get to show anyone what they’ve done. It wasn’t supposed to be this way. It’s an alluring thought, really: It wasn’t supposed to be this way. It gives us permission to not only grieve the dream, but to also hold onto the perfection that never came to be, to allow it to live, at the very least, in the space of our own imagination. But this is where the danger lies. This is a a temptation I succumb to often, the longest-running show in my imagination: The Way Things Were Supposed to Be, starring Kirstyn Wegner, playing nightly to sold-out audiences and rave reviews. I am guilty of preferring this imagined version of events over the reality of what is. I have invested more fully in the “supposed to be” scenarios than I have in what is. I still harbor an insanely irrational hope that I’ll wake up and things will be different, that the order of the universe will have realigned in my favor somehow and things will finally be the way they are “supposed to be”: Peter Pan will go on as scheduled. Regular school is in session, and society is bustling. COVID is gone. Friends are closer than a screen or phone call away. I don’t have epilepsy, I still have my teaching job, and I have my own biological children. I know that none of this is true, mind you. “Supposed to be” was never real in the first place. It's a hard truth to swallow. I never really had any of these things. But that does not make them any less heavy to bear. What is can be a disappointment. In fact, it almost always is, because it’s never what we expect. But “supposed to be” is just a collection of trophies I’ve never won, and that is a heavy cross to bear. This is the weight of “supposed to be.” Each “supposed to be” carries the expectations that created it, and those expectations are burdensome and hard to part with, even as we watch our “supposed to be's” pass into ether. I did not want to put those trophies down. Instead, I held onto them with tight fists. Letting go of them felt like a betrayal, like I was abandoning my dreams. There is an exchange that needs to happen at this point: “Supposed to be” has to die. We have to set those heavy trophies on fire. Only then can we exchange those ashes for the strange beauty of what is, which is nearly always wrapped in disappointment. It is only after we can shed that husk and accept what’s actually inside that we can begin to learn to enjoy it. What is is all around you, just waiting for you to embrace it, to explore it, to experience it. If you are present and brave enough to make this divine exchange, you will see how much it can teach you. Light those “supposed to be’s” on fire. Do not be afraid to let them burn. |

Old Stuff.

January 2023

Categories.

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed